So turns out, the people telling you things online aren’t always talking out of their ass. Especially the old dudes lingering about on weird electrical engineering forums.

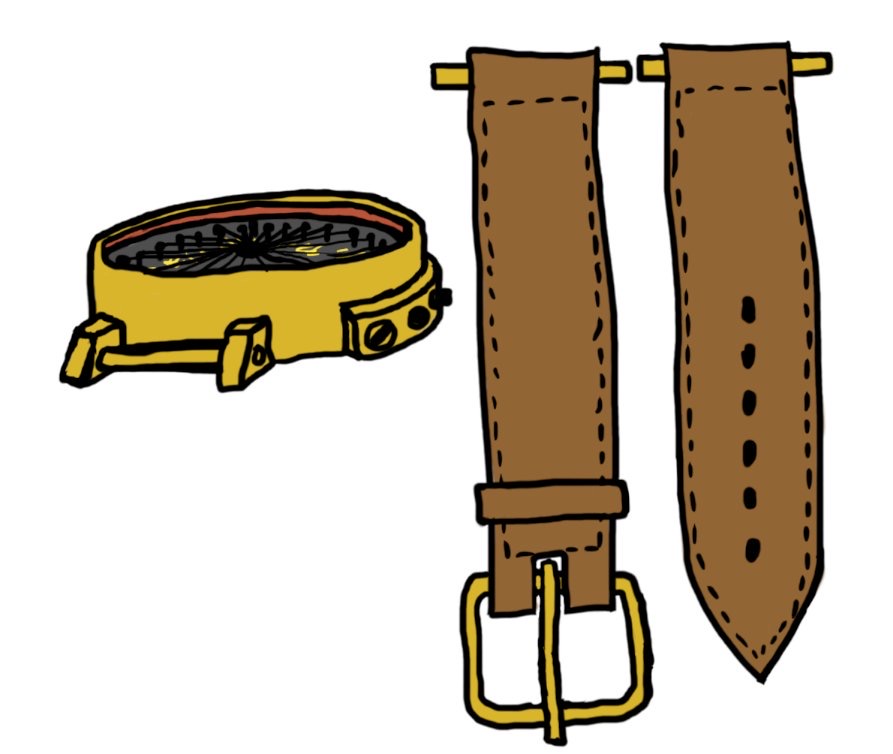

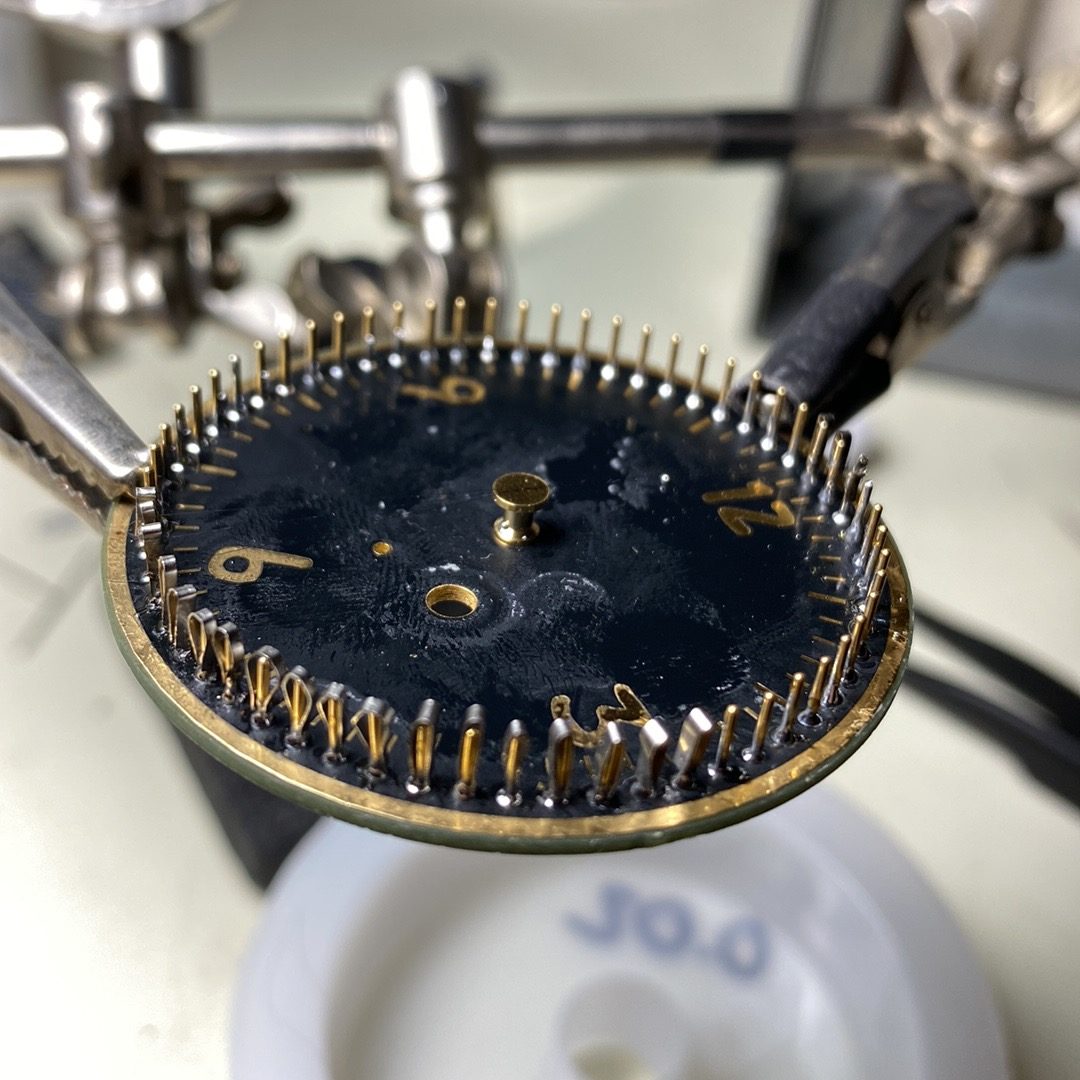

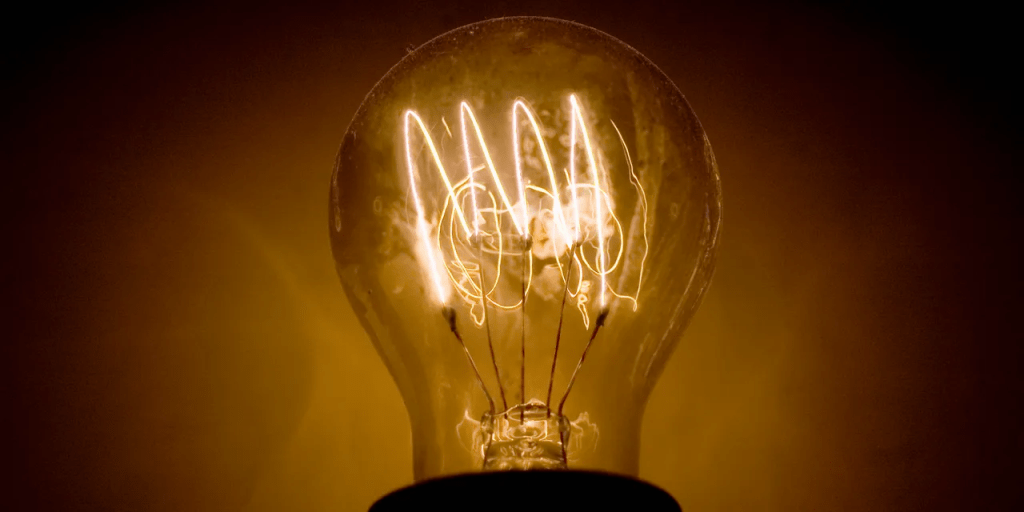

Successful “High” vacuum is an absolute must for the project I have been calling the “Watch Project”. It’s something that’s been off and on for a few years. Basically, it’s 60 light bulb filaments all setup like second hands on an analog watch and I’m trying to pack it all into a wrist watch sized device. (You’re supposed to put the horse in behind the cart right?) Here’s an incandescent 7-segment display called a Numitron that uses super thin coiled tungsten filaments to achieve a similar goal to the watch idea. It’s incredibly pretty in the dark.

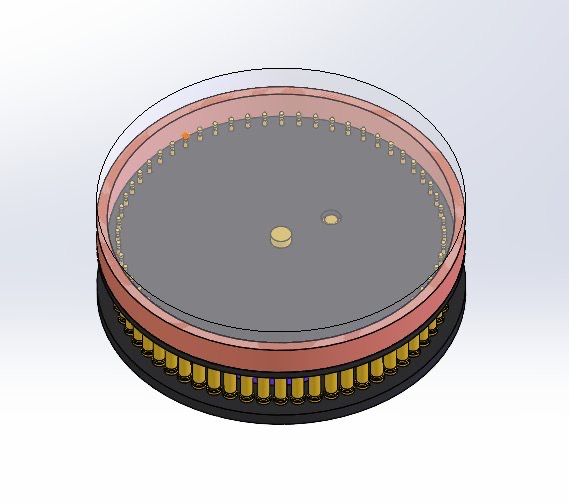

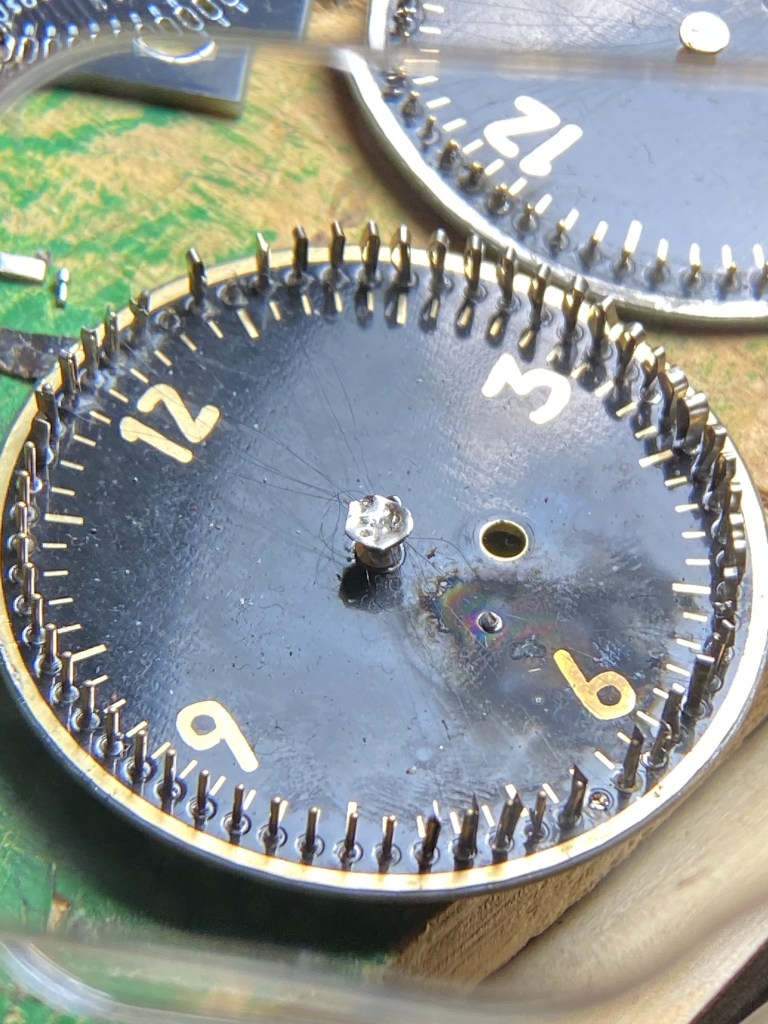

I will go into more detail on this idea in another post, but for now, the important thing is I need to make a good enough vacuum where the filament doesn’t just burn up first. Here’s a little teaser.

For those not passionate about incandescent light bulb design, I’ll give you some context for the issues I’ve been running into.

If an incandescent light bulb were to be turned on with a perfect vacuum in the bulb (absolutely zero gasses or crud floating around), the glowing hot filaments inside would evaporate onto the walls of the bulb. The evaporation slowly wears down the filament over time until the connection breaks, and the bulb burns out. This means filling the bulb with an inert gas (in my case Argon) is ideal for a long lasting bulb.

Additionally, if the bulb is turned on and there is water and oxygen inside the bulb, the filament will oxidize, create free floating Tungsten-oxide, and will then deposit on the walls of the bulb. If hydrogen is present, the oxygen will separate from the tungsten-oxide, creating H2O. When that water molecule comes in contact with the filament again, the oxygen will separate from the water molecule, and repeat the cycle of filament death. This is why only traces of oxygen and water vapour present inside a bulb will do a lot of damage to a filament over time. (or in my case within 60 seconds)

Due to Laziness and avoidance of an exploding project scope, I tried to see if the absolute bare-minimum of vacuum technology (mason jars and Princess Auto plumbing fittings) was enough to achieve the previously mentioned level of vacuum.

It was not. This is where I should have listened to the old dudes, and perhaps my refrigeration tech friends, instead of thinking I was clever.

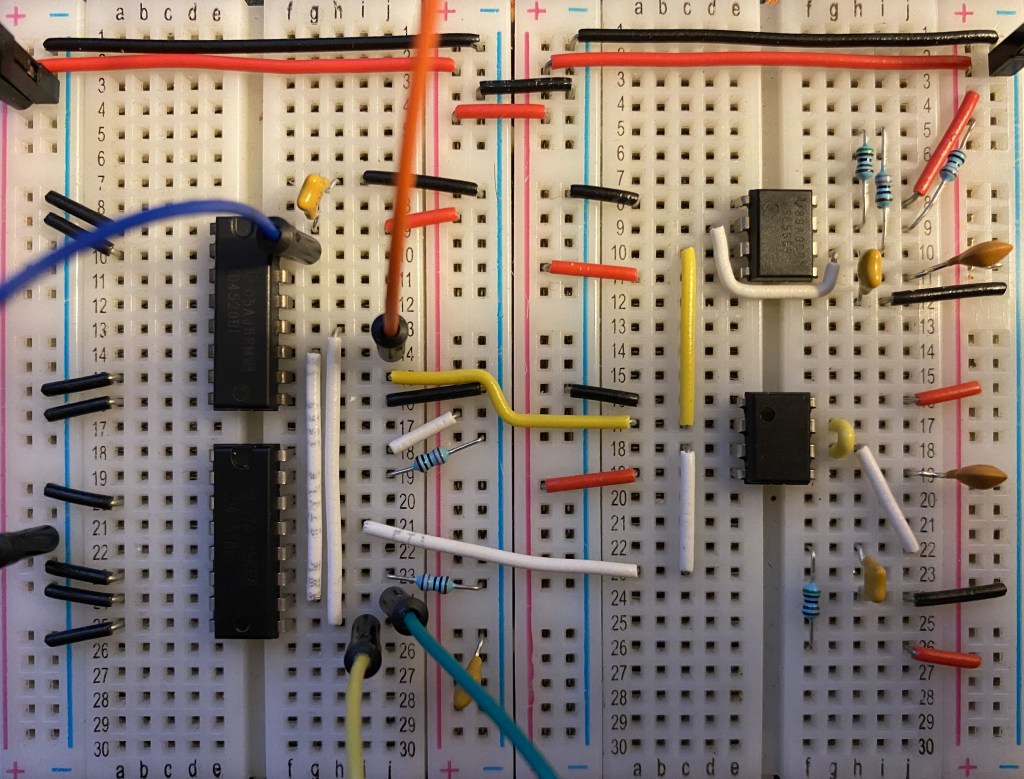

No matter how much Gasket maker, Teflon tape, and plumbing fittings I threw at my custom mason jar vacuum chamber, I simply could not achieve high enough vacuum without something leaking. Although the vacuum dial was maxed out in my final trials, light bulbs require much much higher vacuum than any standard dial gage could show you. Even though I tried to flush out the system with Argon (the inert gas of choice), the imperfect seal was letting the smallest amount of oxygen attack my test filaments. Below is the vacuum chamber setup, and the scraggly aftermath of the burnt up test filaments.

The main take away from this work is:

1) One cannot underestimate how difficult achieving high vacuum is.

1.2) Why it took so god damn long for the boys to figure out how to make lightbulbs

2) I need a way of measuring medium-high vacuum

3) I need a vacuum system that connects to my watch design with absolutely zero leaks while under high vacuum

I have recently purchased an old High vacuum measuring device, and the glass tubing and epoxy required to achieve the next level of Vacuum. Those parts are on their way and hopefully they will be the answer.

– Ben

Credits:

Light bulb photo: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/incandescent-light-bulb-ban-what-you-need-to-know

Info regarding evaporation of Tungsten filament:

Raymond Kane, Heinz Sell Revolution in lamps: a chronicle of 50 years of progress (2nd ed.), The Fairmont Press, Inc. 2001 ISBN 0-88173-378-4 page 37, table 2-1

Leave a comment